This is a question that has been, is being, or will be asked by many people who believe in God or a Creator. Who created the Creator? Who created God? The question may seem valid. Syntactically, it is well-formed. But it does not make sense.

Not all grammatically correct questions are logically valid. For example: “Do you remember what you ate yesterday?” — This is both grammatically correct and logical. But “Do you remember what you died yesterday?” — While structurally identical, this question is nonsensical. The phrase “what you died” lacks semantic coherence.

Here are more examples of grammatical absurdities:

- “How many meters are in a liter of water?” — Syntactically correct, but illogical since volume cannot be measured in meters.

- “How do I not forget places I’ve never been?”

- “What does a triangle with four angles look like?”[1]

These are all examples of contradictory or impossible ideas, masked by grammatically valid phrasing.

So, when someone asks[2], “Who created God?”, what they are really asking—unknowingly—is, “Who created the uncreated Creator?”

And the only logical answer is: If anything created that “god,” then that creator would be the real God.

In other words, the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—the God Jesus called Father, the Creator described in Genesis—was not created. That is precisely what defines Him as God: He simply IS. “I AM WHO I AM” (Exodus 3:14)

He did not give Moses a name in the ordinary sense—like chair, table, Carlos, Ra, or Toth.

“I AM” is not a name, but a revelation of His nature: He exists by necessity, not by creation.

Therefore, asking “Who created God?” is a contradiction—it assumes that God is a contingent being, like everything else in creation, when by definition, He is necessary.

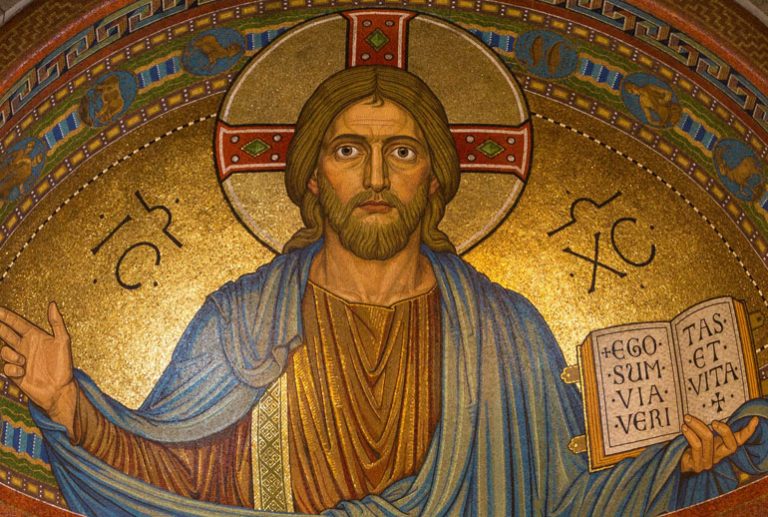

All things that have existed, exist now, or will exist in the future share a property called contingency. This means they might exist or might not.

I am contingent—I exist, but I might not have existed. The door of your house is contingent—it exists, but you could have a different one. The sun is contingent—if it did not exist, we would not either, but the rest of the universe might.

God, on the other hand, is not contingent. He does not depend on anything for His existence. He is eternal and self-existent. He is necessary—the opposite of contingent.

In his exposition of the Five Ways to prove the existence of God, Saint Thomas Aquinas refers to God as the First Cause[3]. For there to be contingent beings like us, there must be a non-contingent being that caused them all. If we exist, then the One who must exist—God—cannot not exist.

So, when someone asks, “Who created God?,” they are unknowingly trying to apply the rules of contingency to a being that is necessary. It is like asking: “What is the tastiest food you’ve never tasted?” or “How do I remember something that never happened?”

These are self-contradictory questions. The same applies to “Who created God?”

It is important to be cautious with questions that contain built-in contradictions because they can unsettle believers who are not prepared to see the logical error in them.

One classic example is: “Can God create a stone so heavy that He Himself cannot lift it?”

This question is not a genuine test of omnipotence. It misunderstands what omnipotence means. God’s omnipotence does not include the power to do the logically absurd—like making a square with three angles or a living dead person. These are not real things; they are conceptual contradictions.

The same goes for the immovable stone. The question is designed not to explore truth, but to confuse and cast doubt. Once we understand the logic behind omnipotence, the malicious intent of the question is easily disarmed.

The same can be said of the question: “What was God doing before the creation of the universe?”

Saint Augustine famously quipped: “He was preparing hell for those who ask such questions.”

But in theological terms, the question cannot be answered, because time itself was created when God created the universe. The concept of “before” only makes sense within time—and time did not exist until God willed it into being.

[1]In his Summa contra Gentiles, Saint Thomas Aquinas wrote: “Since the principles of certain sciences—such as logic, geometry, and arithmetic—are derived solely from the formal principles of things, upon which their very essence depends, it follows that God cannot perform actions contrary to these principles. For example, from a species, the genus cannot be predicated; it is impossible that lines [radii] drawn from the center of a circle are not equal, just as it is impossible that the sum of the internal angles of a triangle does not equal two right angles.”

[2]In Christianity, the term god (in lowercase) is often used as a synonym for “idol.” In this paragraph, I have emphasized the distinction by using bold type to highlight the initial letter—God (uppercase) refers to the one true God in Christian belief, while god (lowercase) denotes a false deity or idol.

[3]Long before Saint Thomas Aquinas, Aristotle—writing in the 4th century bc—was among the first philosophers to speak of a primary cause.