The first element of this sorrowful scene is a corpse: Jesus died on the cross. Some opponents of the resurrection argued that the Master did not actually die but merely survived the crucifixion and was taken down from the cross while still alive.

However, a significant medical study challenges this notion. Dr. William Edwards, Dr. Wesley Gabel, and Dr. Floyd Hosner, pathologists from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, published a detailed report on the physical death of Jesus. Their findings appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association, in the issue dated March 21, 1986 (recap):

Let us first consider the physical condition of Jesus. The demands of His ministry, including extensive travel on foot across the land of Israel, would have been impossible without robust health. We can reasonably assume that Jesus was in excellent physical condition prior to His arrest in the Garden of Gethsemane.

Following His arrest, however, a cascade of physical and emotional trauma began: emotional stress, sleep deprivation, lack of food and water, severe beatings, and the long walk to Golgotha all made Jesus more vulnerable to the devastating physiological effects of Roman scourging.

The Gospels report that in Gethsemane, Jesus experienced such agony that He sweated blood—a phenomenon known today as hematohidrosis (bloody sweat) (cf. Matthew 26:36–38; Luke 22:44). Science identifies this condition as a rare, stress-induced hemorrhaging of the sweat glands, which leaves the skin extremely fragile.

According to the medical report, during the scourging, Jesus suffered deep lacerations inflicted by a flagrum— a whip consisting of multiple leather thongs with metal balls and bone fragments at their ends (cf. Matthew 27:24–26). These whips wrapped around the victim’s torso, tearing into the subcutaneous tissue and even skeletal muscle, inflicting wounds so severe that the body was often left on the verge of circulatory collapse or death.

The volume of blood loss during scourging was a determining factor in how long a victim might survive on the cross. In Jesus’ case, the extent of the blood loss likely brought Him into a state of hypovolemic shock—a condition where blood volume is critically low, reducing the heart’s ability to pump effectively.

Adding to the trauma, the Gospel of Matthew recounts that Jesus’ wounded back was covered with a cloak by the soldiers, only to be ripped off later, reopening and aggravating His injuries (cf. Matthew 27:27–31).

At the crucifixion site, Jesus’ arms and legs were fully stretched. Nails were driven between the radius and carpal bones of the wrists. Though no bones were broken, the periosteum—a highly sensitive membrane covering the bones—was likely pierced, causing intense pain. The nails probably severed the median nerve, producing fiery nerve pain in both arms and rendering part of His hands paralyzed, causing a “claw-like” hand deformity.

The nails in His feet likely pierced His tarsal bones, also injuring major nerves and contributing further to His pain. But the most critical effect of crucifixion was on breathing. The body was fixed in a position that made exhalation extremely difficult, resulting in shallow breathing, muscle cramps, and progressive asphyxiation.

According to the Gospel of John, when a Roman soldier pierced Jesus’ side with a spear, a sudden flow of blood and water was observed (cf. John 19:34). From a modern medical perspective, this indicates that the spear likely penetrated the right lung, the pericardium, and the heart, ensuring death.

Considering these findings, the suggestion that Jesus merely survived the crucifixion is incompatible with modern medical knowledge. The physiological evidence described by Drs. Edwards, Gabel, and Hosmer, and affirmed by the Gospel witnesses, confirms that Jesus was indeed dead when taken down from the cross

Roman soldiers were so accustomed to death that they could easily recognize it. They knew, beyond doubt, when someone had died. This explains the reaction of the Roman centurion standing before Jesus at the moment of His death: “Truly, this man was the Son of God.” (Mark 15:39)

It was likely this same soldier who later confirmed Jesus’ death to Pontius Pilate, allowing him to release the body to Joseph of Arimathea when he came to request it:

Pilate was surprised to hear that He was already dead, and he summoned the centurion and asked whether Jesus had already died. When the centurion confirmed this, Pilate granted the body to Joseph. (Mark 15:44–45)

The second element in this scene is the tomb where the body of Jesus was placed late on that Friday afternoon. The word “tomb” appears thirty-two times in the biblical accounts of the resurrection—underscoring the central importance the apostles placed on this location.

The Church historian Eusebius of Caesarea, known as the “Father of Church History,” recorded in his work Theophany a description of the tomb as relayed to him by Empress Helena, the first imperial patron of the Holy Sepulchre:

The tomb itself was a cave that had been carved out; a cave that had been cut into the rock and had not been used by anyone else. It was necessary that the tomb, which in itself was a marvel, cared only for a corpse.

In March 2016, the six Christian orders that share custodianship of the Holy Sepulchre—the Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Armenian Apostolic, Syrian Orthodox of Antioch, Coptic, and Ethiopian Churches—granted permission to a team from the National Technical University of Athens to inspect and restore the Edicule, the structure that covers the tomb.

The restoration project, which cost over $4 million, was financed in large part by King Abdullah II of Jordan and a $1.3 million donation from Mica Ertegun[1] to the World Monuments Fund. While the archaeologists concluded that it is not possible to verify with absolute certainty that the current site is the exact location of Christ’s burial, they affirmed that the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and the tomb it encloses occupy the same area identified in the fourth century by Saint Helena and her son, Emperor Constantine.

When Helena and her entourage arrived in Jerusalem around ad 325, their search led them to a Roman pagan temple, built approximately two centuries earlier. The structure was dismantled, and beneath it they discovered a rock-cut tomb within a limestone cave. To reveal the burial chamber, where the body of Jesus had been laid on a stone bench, the upper portion of the cave was removed. To preserve this sacred place, the Edicule—a small shrine-like structure—was built over the tomb. That structure, with many restorations, remains standing to this day.

During the 2016 restoration, samples of mortar from the Edicule were extracted and dated in two independent laboratories. The analysis confirmed that the construction materials dated back to the fourth century. This finding supports the continuity of the site, indicating that the location venerated today as the tomb of Jesus has remained the same for over 1,700 years, despite enduring numerous attacks, collapses, and reconstructions throughout its long history.

The third element of the scene is the grave. Remarkably, we know more about the burial of Jesus than we do about the burials of any other prominent figures of antiquity—including pharaohs, kings, emperors, and philosophers.

We know who took possession of Jesus’ body after His death was officially confirmed. We know the name of the man who donated the embalming spices, as well as the amount he donated. The individuals involved in the burial preparations, following the customary rites of the time, are also recorded by name.

We know who owned the tomb, including his place of origin, religious affiliation, economic status, and profession. We know the precise location of the tomb, and we are told how many times it has been used previously. We even know the material from which it was made.

The approximate day and time that the body was laid in the tomb are preserved in the Gospel record. We know how the tomb was sealed, and who was assigned to guard it for three days.

Such a level of historical detail regarding a burial is unmatched in the ancient world. No other figure from antiquity, regardless of status or legacy, has had the circumstances of their burial preserved with such specificity.

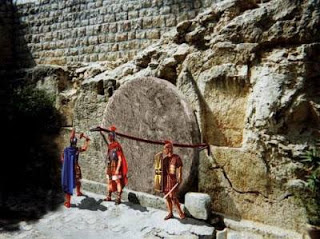

The fourth element of the scene is the stone. It is known that the stone was round, large, and extremely heavy. This explains the concern of the women who, on their way to the tomb, wondered who would roll it away.

The tomb could be entered upright, without the need to bend down, suggesting that the stone had a diameter of approximately five feet, or more. Based on this size, its thickness would have been at least twelve inches. With these dimensions, the stone would have weighed more than two tons—an object far too heavy to move without significant effort.

This assessment aligns with the Gospel descriptions: “And he rolled a large stone across the entrance to the tomb.” (Matthew 27:60) and “They looked up and saw that the stone, although it was extremely large, had already been rolled back.” (Mark 16:4)

The fifth element in the scene is the seal. I will dedicate the following thesis exclusively to this subject, as it holds great importance in understanding the full context of the burial and resurrection narrative.

The sixth element of the scene is the guard. Because Jesus had repeatedly announced that He would rise from the dead on the third day, the Sanhedrin feared that His disciples might attempt to steal the body. If the corpse were to disappear, they reasoned, the disciples could then proclaim the much-anticipated resurrection of the one who had claimed to be the Son of God.

For this reason, the Sanhedrin succeeded in convincing Pontius Pilate to assign a “guard troop” to monitor the tomb—meaning Roman soldiers. Given the concern that all twelve apostles, or at least the remaining eleven, might attempt such a theft, the number of soldiers had to be proportional to the perceived threat.

A precedent for such proportional guarding is found in the Acts of the Apostles, when King Herod placed Peter under arrest and had him guarded by sixteen soldiers:

About that time, King Herod began a persecution of certain members of the Church. He had James, the brother of John, put to death by the sword. Seeing that this pleased the Jews, he proceeded to arrest Peter also. […] After arresting him, he put him in prison and assigned four squads of four soldiers each to guard him. (Acts 12:1–4)

It is reasonable, then, to assume that a similar number of soldiers—between four and sixteen—was assigned to guard the tomb of Jesus.

The Strategikon, a Roman military manual, describes the punishment for a soldier who fell asleep on watch: a brutal form of discipline called animadversio fustium, in which the offender was publicly beaten with rods until he lost consciousness. This harsh reality helps explain why the jailer of Paul and Silas, believing they had escaped after an earthquake, drew his sword to take his own life:

When the jailer was roused from his sleep and saw the doors of the prison wide open, he drew his sword and was about to kill himself, thinking that the prisoners had escaped. (Acts 16:27)

The historian Polybius[2] records that a guard troop typically consisted of four to sixteen men, who were relieved every eight hours. These Roman soldiers assigned to Jesus’ tomb would have been fully aware of the consequences of failing in their duty.

Is it plausible to believe, then, that all of them fell asleep simultaneously, and that no one awoke while the disciples rolled away a massive stone and removed the body?

The whole scene of the burial place of Jesus has enormous historical support. Never has a criminal produced so much concern after his execution. Above all, someone condemned to die on the cross had never had the honor of being guarded by a squad of soldiers. All judicial and police measures at the time, in addition to those dictated by prudence, were taken to prevent the corpse of Jesus from moving even one inch from the place where it had been deposited that Friday. Even so, three days later, the body was gone.

Today we can feel with our own hands the rock of the place where Jesus was enshrouded and touch the stone on which his body rested in that tomb, which is still empty.

[1]She is the widow of Ahmet Ertegun, a Turkish-American businessman and music producer. Ertegun was best known as the co-founder and president of Atlantic Records, the influential record label that helped launch the careers of iconic artists such as Ray Charles, Led Zeppelin, Phil Collins, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.

[2]Polybius (Megalopolis, Greece, bc 200 – 118) was a Greek historian considered one of the most important figures in the field of historiography. He is credited with writing the first true universal history, aiming to explain how Roman hegemony came to dominate the Mediterranean world. To achieve this, Polybius demonstrated how political and military events across various regions were interconnected, presenting a cohesive and comprehensive account of the rise of Rome.