Deciphering the mystery of the empty tomb and the post-resurrection appearances is key to demonstrating that the resurrection of Jesus was a historical event. As the Apostles’ Creed affirms, “He was crucified, died, and was buried,” and three days later, His body was no longer in the tomb.

What happened? Where is the body?

How can we explain that, despite all the measures taken by the authorities to protect the tomb, its contents disappeared on the third day?

The New Testament records multiple appearances of the risen Lord following His departure from the grave. Some of these were personal encounters—with Peter, Mary Magdalene, James, and very likely with His mother. Others were public, including one before a group of more than five hundred followers:

Afterward, He appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, although some have fallen asleep. (1 Corinthians 15:6)

The Bible is not the only source that mentions witnesses to the resurrected Christ. Several ancient historians also refer to these events, including Flavius Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews, Cornelius Tacitus in Annals, and Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (Pliny the Younger) in his letters to Emperor Trajan, among others[1].

The witnesses did not describe vague “sightings” or abstract visions. They spoke of encounters—of interactions with someone they recognized as real and alive, someone who spoke, walked, and ate with them.

- In the first appearance, to Mary Magdalene (John 20:11–18), Jesus spoke with her by name.

- In the second, to a group of women (Matthew 28:8–10), they spoke with Him and even clung to His feet.

- In the third, on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:13–33), He walked with two disciples, explained the Scriptures, and shared a meal with them.

- In the fourth, with ten of the apostles gathered (John 20:19–22), Jesus showed them His wounds and ate with them.

- In the fifth, He appeared again to the apostles—this time with Thomas present (John 20:26–29). Jesus invited Thomas to touch His hands and place his hand into His side.

- The sixth appearance took place by the Sea of Galilee, where seven disciples were fishing. Jesus joined them and shared a meal.

Though these appearances were of a “transformed” body—a mystery that took the disciples time to fully grasp (cf. 1 Corinthians 15:38–57)—it was still clearly a real, physical body. He spoke, reasoned, walked, and ate. It was the body of a living person.

Throughout history, all kinds of theories have been proposed to explain the empty tomb—ranging from the fanciful to the more seemingly plausible. However, those who seek to dismiss the miracle of the resurrection are confronted with the challenge of fitting all the available evidence into their alternative explanations.

It is essential to emphasize the word “all”, because any theory that accounts for only part of the evidence cannot be stronger than one that explains the entire historical record. A credible hypothesis must encompass every relevant fact to be considered serious.

Let us examine some of the more popular non-resurrection theories that have attempted to explain the empty tomb:

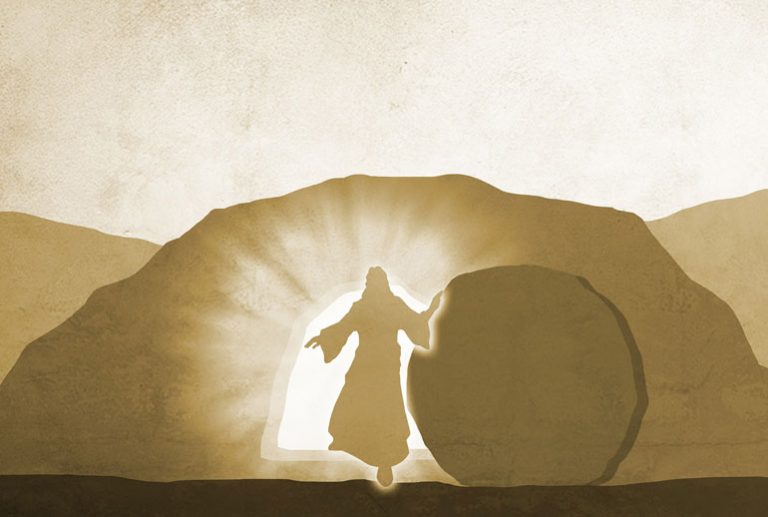

- The Catalepsy Theory: Popularized by a heterodox Muslim group known as the Ahmadiyya Community, this theory claims that Jesus did not actually die on the cross but fell into a state of catalepsy, later waking up inside the tomb. According to this view, He exited the tomb by His own means and reunited with His disciples. However, this theory is contradicted by the position and condition of the burial cloths, as described by the beloved disciple—a detail I will explore in a later section. It is also logistically implausible: a severely wounded man could not have moved a two-ton stone, let alone from the inside. If this had occurred, the Roman guards would not have run to the chief priests to request help fabricating an explanation to avoid the consequences they faced for allowing the body to disappear.

Furthermore, as discussed in the fourth thesis of this chapter, a detailed medical report confirms that Jesus died on the cross. - The Hallucination Theory: Proposed by the French theologian and orientalist Joseph Ernest Renan in the late 19th century, this theory asserts that the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus were hallucinations, brought on by the disciples’ overwhelming emotional trauma.

However, as previously noted, the Gospel accounts describe not mere “sightings” but interactions—spoken conversations, physical contact, shared meals. The witnesses testified not to visions, but to encounters with someone alive, tangible, and reasoning. - The Wrong Tomb Theory: This idea, advanced by Kirsopp Lake, a professor of New Testament at the University of Oxford in the mid-20th century, claims that the women mistakenly went to a different, empty tomb.

This theory fails to account for the numerous post-resurrection appearances of Jesus. The Gospels clearly show that the disciples themselves initially thought they were seeing a ghost[2], but Jesus dispelled that idea: “While they were still speaking about these things, Jesus himself stood in their midst and said to them, ‘Peace be with you!’ In their panic and fright, they thought they were seeing a ghost. But He said to them, ‘Why are you disturbed? Why do such doubts arise in your hearts? Look at my hands and my feet, that it is I myself. Touch me and see; for a ghost does not have flesh and bones as you see I have.’” (Luke 24:36–39).

Jesus invited them to touch Him—He wanted to make clear that He was not a spirit, but present in body and soul. He even asked them for something to eat, and they gave Him a piece of roasted fish, which He ate in their presence. The text leaves no doubt: what they saw was not a ghost, but Jesus in His resurrected, still-wounded body.

Another point that undermines the “wrong tomb” theory is that the women knew the tomb well. The Gospels affirm their presence at the burial: “The women who had come with Jesus from Galilee followed and saw the tomb and how his body was laid in it.” (Luke 23:55) or “Mary Magdalene and the other Mary remained sitting there opposite the tomb.” (Matthew 27:61) - The Qur’an’s Version: Islam offers its own version of events regarding Jesus’ death and the empty tomb. In the Qur’an, Jesus is known as ‘Isa ibn Maryam’, meaning “Jesus, son of Mary.” The story begins with his grandmother Ana, who dedicated her daughter Mary to the service of the temple before her birth. Mary, shown to be deeply devoted to God, miraculously conceived Jesus while still a virgin, after being visited by an angel.

According to the Qur’an, Jesus grew in wisdom, became a prophet, was called the Messiah, and performed many miracles. Eventually, He was flogged and sentenced to death by crucifixion—but He survived. His disciples secretly healed Him, and He escaped to continue His mission to the lost tribes of Israel. Under the name Yuz Asaf, He traveled east, eventually reaching Kashmir, India, where He is said to have died at the age of 120. Today, a modest shrine in Srinagar, a city in northern India, marks what some believe to be His tomb. It receives few visitors.

In addition to the arguments above that challenge these theories, we must also consider that, after the resurrection, Jesus’ body was no longer the same. It could pass through locked doors, something that deeply impressed the apostles. The Gospels tell us:

In the evening on that same day, the first day of the week, the doors were locked in the room where the disciples were, for fear of the Jews. Jesus came and stood in their midst and said to them, ‘Peace be with you!’ (John 20:19, emphasis mine)

Lastly, we cannot forget that the disciples also witnessed His ascension:

As He said this, He was lifted up while they looked on, and a cloud took him from their sight. While they were gazing up into the sky as He was going, suddenly two men dressed in white stood beside them and said, ‘Men of Galilee, why are you standing here looking up into the sky? This Jesus who has been taken from you into heaven will return in the same way you saw him go to heaven.’ (Acts 1:9–11)

It should be clear by now that these theories may account for some of the evidence—but not all. And as mentioned earlier, partial explanations cannot outweigh a theory that fits the full body of available facts.

To the list of alternate explanations for the resurrection, there is one more that deserves special attention—because it is found in the Gospels themselves:

While the women were on their way, some members of the guard went into the city and reported to the chief priests all that had happened. After meeting with the elders and formulating a plan, they gave a large sum of money to the soldiers and instructed them, ‘You are to say, “His disciples came during the night and stole him while we were asleep.” If the governor hears of this, we will placate him and protect you from any trouble.’ The soldiers accepted the money and did as they were instructed. And this story is still told among the Jews to this very day. (Matthew 28:11–15, emphasis mine)

An empty tomb, in itself, does not conclusively prove that a resurrection occurred. But it does raise a profound question: Was the disappearance of Jesus’ body the result of divine action or human interference?

The facts are simple. Jesus was buried, anointed, and wrapped in a linen shroud on Friday, before sundown, in a tomb donated by Joseph of Arimathea. When the women returned on Sunday morning to complete the burial rites—cut short due to the onset of the Sabbath—the body was no longer there.

This situation presents two explanations:

- Someone entered the tomb and removed the body — a human act, a theft.

- Jesus rose and left the tomb by His own power — a divine act, the resurrection.

If the first option is true—if it was a robbery—then the natural question follows: Who removed the body? Only two groups of people could be considered suspects: His friends or His enemies.

Throughout history, the desecration of graves has unfortunately been a common crime, and it continues in many parts of the world today. However, it is essential to recall that the tomb of Jesus was, in effect, Roman territory—under the authority and laws of the Empire. And Roman law severely punished those who tampered with graves. Offenders faced fines ranging from 100,000 to 200,000 sesterces, a staggering amount[3].

To better understand the severity of this penalty, consider the following: According to Tacitus (Annals, Book I, chapters 17:4–5), Roman soldiers stationed along the Rhine were paid four sesterces per day—a wage that had to cover even their own uniforms. A British writing tablet dated ad 75 records the sale of a slave named Vegetus for 2,400 sesterces. In this context, a fine of 100,000 or 200,000 sesterces would have been economically devastating for any individual—making grave robbing a high-risk crime.

Moreover, this tomb was not just any tomb: it had been officially sealed by Roman authority. The seal bore the imperial insignia, and breaking it was equivalent to defying the emperor himself.

Who, then, would have dared to approach the stone—let alone move it?

[1]In the previous chapter, I included the corresponding bibliography for these historians and others.

[2]Some Bible translations use the words “ghost” or “spirit,” though their meanings can differ significantly. The term “ghost” is often associated with demonic entities, whereas “spirit” can have a broader range of meanings. For example, expressions like “Spirit of the Lord” or “Holy Spirit” refer to God Himself. However, the term “spirit” can also appear in negative contexts, as in the phrase “unclean spirit,” which refers to a demon.

[3]Actio de sepulchro violato (“action for violation of a tomb”) was a legal remedy in Roman law. The praetor granted this action against anyone who intentionally violated, inhabited, or built upon a tomb that did not belong to them. If the rightful holder brought the claim, the penalty was determined as quanti ob eam rem aequum videbitur— “as much as seems fair and equitable for the matter.” However, if the rightful owner chose not to pursue the claim or if no owner could be identified, the praetor permitted a popular action as a subsidiary measure, imposing a fine of one hundred thousand sesterces for violation and two hundred thousand sesterces for habitation or construction. (Source: Roman Law, Gumesindo Padilla Sahagún)