Conclusion

The Book of the Acts of the Apostles, written by Luke—the same author of the Gospel that bears his name—narrates the foundation of the Catholic Church and the spread of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire. After the apostles received the Holy Spirit on Pentecost, they began organizing daily gatherings in homes to celebrate the commemoration of the Lord’s Last Supper: “Day after day they met in the temple, and in their homes they broke bread and shared their food with glad and generous hearts.” (Acts 2:46)

The word “last” before the word supper should naturally evoke a sense of finality—a solemn farewell. And indeed, in the case of the Lord’s Supper, it marked the beginning of the end, as the events that led to His death followed shortly thereafter.

Yet why did the early Christians not gather in mourning, grief, or lamentation to commemorate that moment? Why did they instead celebrate it with joy?

If there had been no resurrection, there would have been nothing joyful to celebrate.

But Jesus had foretold this very transformation:

You are confused because I said: ‘A little while and you will not see me, and again a little while and you will see me.’ Amen, amen, I say to you, you will weep and mourn while the world rejoices. You will grieve, but your grief will be turned into joy. (John 16:19–20)

For many Catholics, the resurrection is just one more article of faith—something believed more out of habit than conviction. In their hearts, they may wonder: How can it be proven that Jesus Christ rose from the dead if it happened so long ago? Or how can we trust that the apostles did not write only what served their purpose?

When these questions arise, many prefer to avoid them, fearing that they challenge the apostles’ honesty. Yet the evidence presented in this chapter provides a foundation strong enough to dispel doubt.

As stated earlier, the Bible is not the only source that testifies Christ was crucified, died, and was buried, and that on the third day, many witnesses reported seeing Him alive, and some of them interacted with Him.

The Gospels give us abundant detail—revealing the honesty, spontaneity, and even the naive of the writers. But they are not the only confirmation of these events. Our faith in the resurrection of the Lord is no longer a leap into the void, but rather a journey along solid ground, supported by strong evidence.

Why, then, does Paul say that if Christ did not rise, our faith is in vain?

Because without the resurrection, there would be no Christianity. There would be no apostles, no Church, and no hope of eternal life. We would still be waiting anxiously for the one who would redeem us from sin and open the way to the Father’s house.

The resurrection of the Lord is decisive.

To understand this, we go back to Abraham, the first man in history to whom God revealed Himself. Before him, people believed in many gods—deities made of stone, metal, or natural forces. But when God spoke, Abraham listened. And the Lord made a promise:

Leave your country, your family, and your father’s house, and go to the land that I will show you. I will make you a great nation. I will bless you and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and I will curse those who curse you. Through you all the families of the earth shall be blessed. (Genesis 12:1–3)

This was the foundation of the promise to the people who would become known as Israel. Although the blessing was intended to reach all the families of the world, Abraham’s descendants would become a “great nation.” God asked only one thing in return: faithfulness.

Every time the Israelites remembered this promise—especially the promise that they would become a great nation—they imagined it in the image of the military and economic power of their age: the Egyptians, the Babylonians, the Greeks, or the Syrians, depending on the period.

Yet despite their expectations, God remained faithful to His covenant, while the Israelite people often did not. And so, generation after generation, they continued to long for the day when they would become great.

Historically, a series of prophets foretold the arrival of a man who would restore dignity to the people of Israel, bring good news to the poor, proclaim liberty to captives, give sight to the blind, and set the oppressed free. This man would not be just any man: He would be God made flesh, the one we would call Emmanuel—the Messiah.

As explained in chapter two, there were hundreds of signs—prophecies given by the prophets—that would help the people identify the long-awaited Messiah. It was also shown that all these predictions were fulfilled in the person of Jesus.

One might assume this would have been sufficient for the people to recognize Him and rejoice, knowing that God was now among men. But the spiritual blindness was such that they did not recognize Him. It fell to Jesus Himself to reveal that He was the one they had been waiting for.

How did the most educated and religious class of Israel—the very ones who knew the Law and the Prophets by heart—respond to this claim?

They regarded Jesus as a madman, an impostor, a blasphemer.

The Jews expected the Messiah to be, at the very least, a figure like King David—a name that in Hebrew means “the beloved” or “the chosen one of God.” David, born in Bethlehem (the same city where Jesus was born) in bc 1040, and who died in Jerusalem in bc 966, was the son of Jesse and Nitzevet. As the youngest of seven sons, he was destined for the low work of shepherding sheep. Yet, he went down in history as a just, brave, and passionate king—a warrior, musician, poet, described in sacred Scripture as “blond, with beautiful eyes, prudent, and of good appearance.” Like all great men, he was not without sin, but he unified the twelve tribes of Israel, completing what his predecessor Saul had begun. Still, during the reign of David’s grandson Rehoboam, the kingdom fractured once more.

This was the resume that the cultured elite of Israel expected in their Messiah.

A poor carpenter, with no wealth and no army, could hardly be imagined as the fulfillment of that hope.

However, the many and extraordinary miracles performed by Jesus caused both confusion and intrigue among the Sanhedrin. They saw Him restore sight to the blind, speech to the mute, hearing to the deaf, strength to the paralyzed, and life to the dead. Clearly, He was not an ordinary man—His works went beyond the natural.

But if His miracles intrigued them, His words infuriated them.

Jesus’ relationship with the religious authorities of Israel fluctuated between intrigue and outrage. At times, they simply ignored Him. But whenever an encounter became inevitable—especially during His visits to the Temple in Jerusalem—Jesus was uncompromising. He openly rebuked them for killing the spirit of the Law given through the prophets. He accused them of turning the Law into a burden, one they themselves were unwilling to bear. He called them: “Hypocrites,” “evildoers,” “faithless,” “fools,” “brood of vipers,” and “blind guides.” He even compared them to whitewashed tombs—beautiful on the outside, but full of corruption within.

One day, the Pharisees and the scribes decided to challenge Him. They demanded another sign, another miracle to prove that He truly was the Messiah. Jesus responded:

An evil and unfaithful generation seeks a sign, but no sign will be given it except the sign of the prophet Jonah. For just as Jonah was in the belly of the great fish for three days and three nights, so will the Son of Man be in the heart of the earth for three days and three nights. (Matthew 12:39–40)

The Master Himself told them that the only sign He would give was His resurrection, not His miracles.

If He rose from the dead, it meant He was neither mad nor deceitful, but truly God incarnate. It meant that everything He had said was the purest truth. It meant that He would not have continually quoted the Scriptures unless those writings were indeed the words of God, entrusted to the prophets by the Father.

It meant that the Law had been reborn, animated now by a new spirit.

It meant that the waiting was over—the one who would redeem us from sin had already come.

It meant that the hope of eternal life with the Father was now a reality.

It meant that the Church, foretold as a bridge between earth and heaven, had been born.

It meant that we could now place our full confidence in everything He promised and hold fast to it.

It also meant that we could call Jesus our brother, Mary our mother, and God our Father.

This is why Paul wrote: “If Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is in vain, and your faith is also in vain.” (1 Corinthians 15:14)

But He did rise.

In the two thousand years since the resurrection of Christ, countless theories have been proposed to distort or reinterpret that event. Some claim that it was merely a story invented by a group of disciples determined to start a new religion based on Judaism—regardless of the cost.

Yet such claims ignore the vast body of evidence—from both Christian and non-Christian sources.

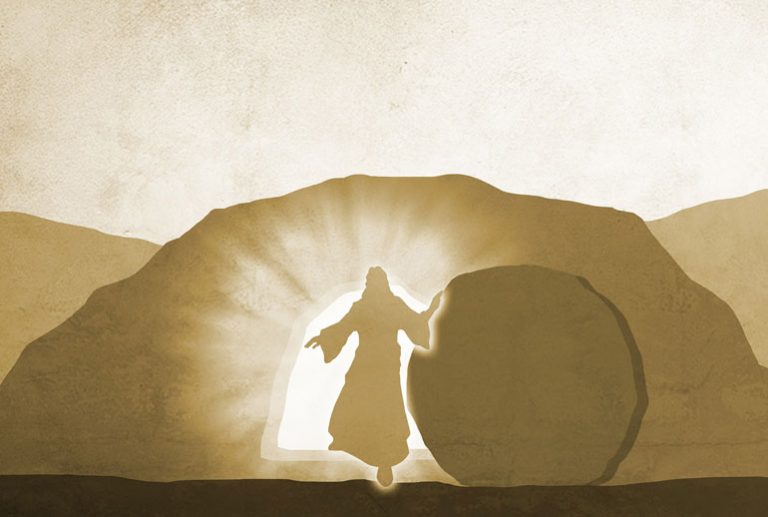

The tomb of Jesus had the imperial seal of the highest Roman authority, making it illegal for anyone to tamper with it without authorization. It was also guarded by highly trained Roman soldiers, operating under the strictest codes of military conduct, watching day and night over the only access to the tomb.

And yet, three days later, those same soldiers went to the chief priests seeking help to create an alibi—to avoid punishment for allowing the body to vanish from the tomb.

Of course, we cannot say that resurrection is the only possible explanation when a body disappears from its resting place. No—such a conclusion should never be entertained lightly.

But this case is unique.

The idea of resurrection could not even be considered unless the event had been clearly prophesied, and unless the deceased had claimed to be God, possessing the power and authority to overcome death and rise again by His own will.

In this chapter, I have presented thirteen carefully developed theses, each one coherent and consistent with the accumulated facts preserved in historical literature, logical reasoning, and Sacred Scripture.

In the second chapter, I demonstrated that the Holy Spirit is the author of the Bible, which means that this unique and sacred book cannot be excluded when gathering evidence to understand the mystery of the empty tomb.

I also cited the testimonies of historians such as Flavius Josephus, Cornelius Tacitus, and Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (Pliny the Younger)—whose writings have survived through the centuries. Though they do not provide the level of detail found in Christian testimony, they nevertheless confirm the essentials—the heart of the matter:

- That Christ was crucified by order of Pontius Pilate

- That He was buried outside the city of Jerusalem, near the place of His execution.

- And that, days later, many people claimed to have seen Him alive.

Likewise, in the previous chapter, I demonstrated that the prophecies spoken by the prophets over several centuries—meant to help identify the Messiah—were fulfilled with the coming of Jesus. I also showed how it is mathematically impossible that these prophecies could have been fulfilled by chance at Jesus’ birth if He were not the Messiah.

I analyzed the facts from every plausible angle: from the possibility that the women went to the wrong tomb, to the suggestion that Jesus had not actually died, to the theory that the body had been stolen. I presented several hypotheses proposed by anti-Christian groups and individuals regarding the empty tomb. Yet, when these theories are confronted with the full body of evidence, each one falls apart.

In every case, there is at least one key fact that does not “add up”:

- That He did not die?

- That people saw a double of Jesus?

- Then where is His corpse?

- Why did the guards have to seek an alibi?

If the body was stolen, someone had to have done it. I examined the only two sides that could have carried this out—His friends or His enemies. But neither theory fully aligns with the facts.

Against all logic and reason, the resurrection remains the only explanation that fully satisfies the evidence.

Jesus made the boldest claim in history: He said He was God.

Not that He was King David, Isaiah, Moses, or Abraham—but God Himself.

Unsurprisingly, many considered Him insane. But after witnessing His many miracles, the people asked Him for one final, conclusive sign—something that would leave no doubt that He was who He claimed to be. And He told them: the resurrection would be that sign. He delivered on that promise. Jesus proved He was God. He proved He was the Messiah foretold by the prophets.

The voice of God, spoken through those holy men, is recorded in the Sacred Scriptures, as is His own voice, through His Son, Jesus Christ.

Can we trust that communication?

Without a doubt.