The philosopher, politician, orator, and writer Lucius Annaeus Seneca, in his tragedy Medea (written in the year ad 56), penned the well-known phrase: “Cui prodest scelus, is fecit” — “He who benefits from the crime is the one who committed it.”

Following this reasoning, the primary suspicion would naturally fall on the friends of Jesus, who would have stood to gain the most from the alleged theft of His body. But did they, in fact, commit such an act?

Given both the direct evidence and the circumstantial factors at our disposal, can we, without violating logic and reason, conclude that the disciples were responsible for removing the body of Jesus?

We are faced with two opposing camps:

- On one side, there were those who sentenced Jesus to death—namely, the Sanhedrin—a group with power, wealth, and an implicit alliance with the Roman government.

- On the other side were the disciples—a small group with no political influence, no legal recourse, and no protection from either civil or religious authorities.

With Jesus’ execution, the Sanhedrin believed they had eliminated the source of the threat. Yet they knew there were still “seeds”—His followers—that might one day take root and spread. But could they eliminate the apostles? Did they have the means to prosecute them?

The answer is no.

The only charge that brought Jesus to death was blasphemy—His claim to be the Son of God. None of His disciples made such a claim. Therefore, there was no religious basis to accuse them of the same crime.

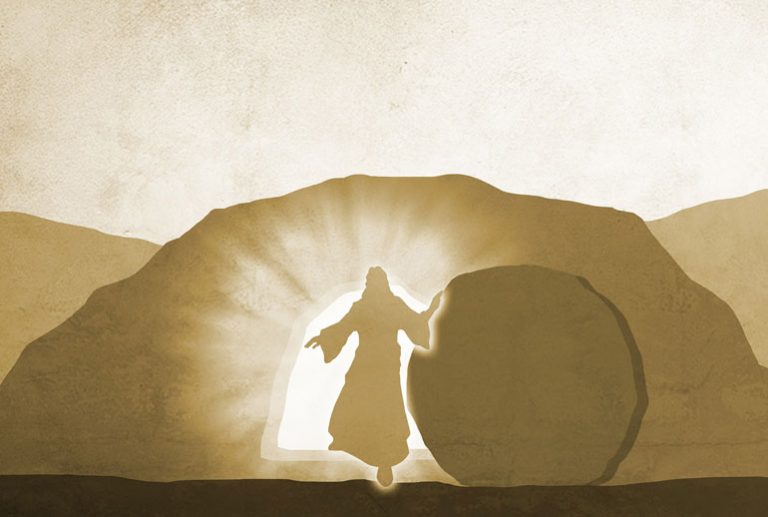

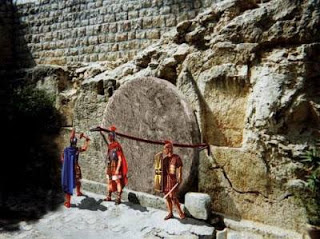

To hand them over to Roman justice, the Sanhedrin would have needed to charge them with a civil offense—something that violated Roman law. And they had the perfect candidate: if the disciples had broken the governor’s seal and desecrated the tomb, this would have constituted a criminal offense, punishable under Roman authority.

As explained earlier, desecration of a tomb was considered a serious crime, and breaking the imperial seal without authorization was an offense that carried the maximum penalty. All the Sanhedrin had to do was provide evidence to Pilate that the disciples were guilty of this transgression, and the governor would have ensured their execution.

But that never happened.

Why?

Because no such evidence existed. And in the absence of proof, the Sanhedrin had no other choice but to bribe the guards, promising them protection in return for their silence and complicity:

They gave a large sum of money to the soldiers and instructed them: ‘You are to say, “His disciples came during the night and stole him while we were asleep.” If the governor hears of this, we will placate him and protect you from any trouble.’ (Matthew 28:12–14)

This fabricated story was their only option. It was a desperate solution born not of strength, but of lack of evidence.