At the beginning of the 20th century, after the fall of the Russian Tsar, a progressive ban on the practice of any religious rites was imposed across the country. Still, certain traditions continued in secret. One of these was the baking of Easter bread, known as Kulich, considered the festival of all festivals by the faithful.

Despite increasing restrictions, believers continued to bake Kulich in varied forms and styles, sharing it in quiet, home-based celebrations with family and friends. However, as communism deepened its grip on every corner of the country, authorities began to aggressively suppress all religious expressions. In some areas, even baking Kulich was prohibited.

One such case occurred in a small village near Kyiv, where in the early 1930s, the local authorities ordered the confiscation of all flour and the shutdown of ovens. Yet, before the raids began, some villagers managed to hide enough flour and ingredients to prepare the sacred bread for the upcoming Easter.

One of the most powerful men in the world at that time was Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin[1], a Russian communist leader and participant in the Bolshevik Revolution. On Easter Day, 1930, Bukharin addressed a mass gathering of workers in a nearby town near Kyiv to promote atheism.

For two hours, he launched an aggressive speech using the “heavy artillery” of anti-religious propaganda, hurling insults, and alleged evidence against the existence of Jesus and the truth of His legacy. When he finally concluded, he stood confidently, believing that all that remained was a pile of broken faith among the listeners.

He asked if anyone had anything to say.

A local priest, hoping to encourage the faithful and inform them that, despite the ban, the Kulich had been baked in secret, asked for a moment to speak. He was given three minutes. He responded that he would need far less than that.

He looked out over the crowd and, with a resounding voice, proclaimed the traditional greeting of the Orthodox Church: “Jesus Christ is risen!”

In a powerful, unified response, the crowd rose to its feet and answered like thunder: “He is risen indeed!”

All the evidence found in the New Testament and in early Church literature confirms that the central message of the Gospel was not “Follow the Master’s teachings and live virtuously,” but rather: “Jesus Christ rose from the dead.”

This is what the apostles went out to proclaim—and it cost them their lives.

What greater testimony could there be that the humble carpenter of Nazareth was neither mad nor a deceiver when He said: “The Father and I are one”? (John 10:30)

Although the Bible records the deaths of only two disciples—Judas Iscariot, the betrayer who hanged himself (cf. Matthew 27:5), and James The Greater[2], who was beheaded by order of King Herod (cf. Acts 12:2)—Tradition tells us that all the others were martyred.

While the places and circumstances of their deaths vary across sources, one consistent point emerges: they all died as martyrs.

Below are the accounts of their deaths, according to the most widely accepted traditions.

John, the beloved disciple of the Lord and brother of James The Greater, is traditionally recognized as the author of the Gospel that bears his name, the Book of Revelation (Apocalypse), and two epistles. According to early Christian tradition, he survived being plunged into a vat of boiling oil, a punishment ordered by Emperor Domitian for preaching the Gospel. When this attempt on his life failed, the emperor sentenced him to forced labor in the mines on the island of Patmos. After some time, John was released, and he later died peacefully on the island of Ephesus.

The martyrdom of Peter was foretold by Jesus Himself, and the evangelist John recorded it in allegorical language: “Jesus said this to indicate the kind of death by which Peter would glorify God.” (John 21:19)

Peter died in Rome, crucified upside down by order of Prefect Agrippa, an official under Emperor Nero. According to tradition, Peter requested this form of crucifixion because he felt unworthy to die in the same manner as his Master.

Andrew, Peter’s brother and son of Jonah, was martyred in Achaia, Greece, in the town of Patras. When Governor Aepeas’ wife and brother converted to Christianity, the governor became enraged. He arrested Andrew and sentenced him to death by crucifixion. Out of humility, Andrew requested a different form of cross than that of Jesus, and so he was crucified on an X-shaped cross, which to this day is known as the Cross of Saint Andrew, one of his traditional symbols. His martyrdom is dated to November 30 in ad 63, under Nero’s reign.

James The Less (also known as Jacobus), the half-brother of Jude Thaddeus and son of Alphaeus and Mary, was martyred in the year ad 62. The high priest Annas ii ordered him to publicly deny Jesus, but instead James began preaching the Gospel from the top of the temple. Enraged, the Pharisees and scribes pushed him from the heights. Since the fall did not kill him, they began to stone him as he prayed on his knees for his executioners. Finally, he was killed by a blow to the head with a mace.

Jude Thaddeus, also known as Lebbaeus, son of Cleophas and Mary, was beheaded with an axe in the city of Suamir, in Persia.

Matthew, also called Levi, the son of Alphaeus and author of one of the four Gospels, was martyred in Nadaba, Ethiopia. He had opposed the marriage of King Hirciacus with his niece Iphigenia, a Christian convert. For this, he was beheaded at the conclusion of a sermon around the year ad 60.

Simon The Canaanite, also known as the Zealot, was martyred in Suamir, Persia, where he was sawn in half.

Philip, originally from Bethsaida, preached throughout Asia and later in Heliopolis, Phrygia (present-day Turkey). He was imprisoned and later crucified there in the year ad 54.

Bartholomew, also called Nathanael, son of Talmai, was martyred in Albana, Armenia. He was first crucified, then taken down before death, flayed alive, and finally beheaded. Because of this, ancient Christian art often depicts him carrying his skin like a cloak, draped over his arms.

Thomas, known as Didymus and sometimes referred to as the doubter, was martyred on the Coromandel Coast of India. His body was found pierced with spears, indicating a violent death for his faith.

The term kamikaze, of Japanese origin, was first used by American translators to describe the suicidal attacks carried out by pilots of the Imperial Japanese Navy against enemy ships toward the end of World War ii. These attacks were intended to stop the advance of the Allied forces across the Pacific and prevent them from reaching Japanese shores. To that end, aircraft loaded with 250-kilogram bombs were deliberately crashed into their targets to sink or severely disable the vessels.

This term has also been used by some journalists to describe certain jihadist terrorists, who seek to kill as many “infidels” as possible while being fully aware that their actions will result in their own deaths. These individuals are motivated by the belief that Allah will reward them in paradise with seventy-two virgins (houris), rivers of wine, honey, and milk, winged horses made of gold and rubies, and other delights meant to satisfy them for eternity.

Beginning in 2009, more than twenty Tibetan monks chose to immolate themselves in protest of the Chinese government’s ban on the return of the Dalai Lama to his native Tibet. For these monks, self-immolation became the only way to draw global attention and pressure the occupying forces to withdraw from their homeland.

In all three cases—jihadist terrorists, Japanese kamikaze pilots, and Tibetan monks—the individuals involved engaged in acts that, while technically suicidal, are often not classified as suicide by those who perform or endorse them. Their religious traditions condemn suicide, but these acts are viewed not as personal despair, but as a sacrifice for a greater, collective cause. In such contexts, the rules are reinterpreted.

However, the case of the apostles is entirely different.

When a jihadist leaves home wearing a bomb vest, fully aware that he will die with his victims, or when a kamikaze pilot intentionally crashes his plane into an enemy ship, or a Tibetan monk binds himself in barbed wire to prevent rescue during his self-immolation, each of them knows with absolute certainty that death is imminent. These are deliberate acts with death as the goal—technically and ethically, suicides.

This was not the case with the apostles.

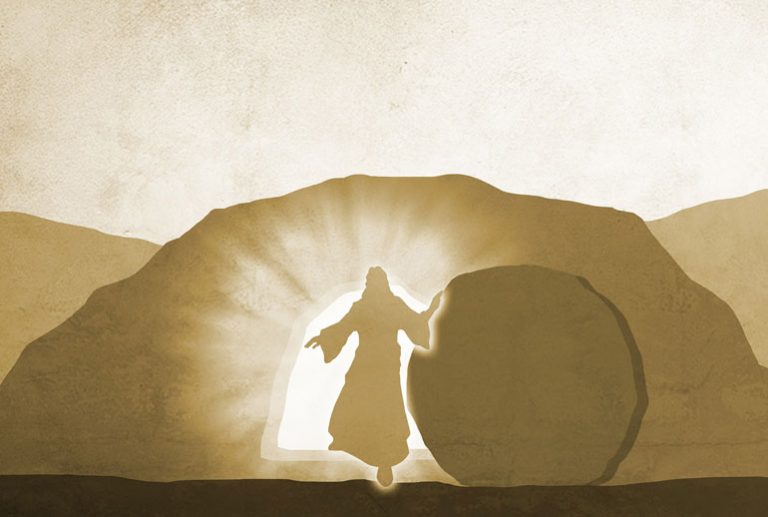

When they proclaimed the resurrection of the Lord, they were fully aware that their message would bring them trouble, and even death—as it did. But they did not seek death, nor did they wish for it. They simply could not deny what had become impossible for them to deny: that they had seen the Master with their own eyes after He had been buried in the tomb so generously offered by Joseph of Arimathea.

The apostles did not give their lives to defend a doctrine, or to preserve the teachings of Jesus, or to protect a nascent Church, much less to safeguard a religion.

They were driven by the reality of the resurrection. They went out into the world to proclaim what they had witnessed firsthand—to recount the life-changing moments they had shared since Jesus of Nazareth entered their lives and called them to follow Him in the most extraordinary experience of their time.

They gave testimony, told the truth of their experience, and for this—they were martyred.

[1]Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (Moscow, October 9, 1888 – March 15, 1938) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary, politician, economist, and philosopher. A prominent figure in the Bolshevik leadership, he served on the Politburo until 1929 and was editor of Pravda. Throughout the 1920s, he was recognized as the chief theoretician of Soviet communism and led the Comintern from 1926 to 1929. Between 1925 and 1928, Bukharin was one of the leading Soviet figures alongside Joseph Stalin. He was a principal advocate for gradual economic modernization and the transition to socialism. During 1928–1929, he emerged as the most prominent representative of the so-called “right-wing opposition” within the Communist Party.

[2]Known as “the Greater,” he was the brother of the apostle John—both sons of Zebedee and Salome. In some Bible translations, his name appears as James.