The way in which death is mourned in the modern Western world contrasts sharply with the customs and attitudes of the ancient Near East. To understand the significance of Jesus’ burial—and the cultural weight surrounding it—it is essential to first explore the funerary practices and expressions of grief in the region during His time.

In first-century Jewish culture, the death of a loved one was met with a profound and emotionally charged response. Mourning began immediately and was often expressed through intense, even visceral lamentation. Ancient sources describe this initial reaction as a high-pitched, ear-piercing wail—a public outcry of sorrow and despair. This dramatic expression of grief had deep roots in Jewish memory, recalling the night of the first Passover in Egypt: “Pharaoh arose during the night, he and all his officials and all the Egyptians, and there was a loud cry of grief in Egypt, for there was not a single house in which someone was not dead.” (Exodus 12:30)

This collective mourning became a ritualized aspect of Jewish bereavement. Family and friends would continue lamenting from the moment the first wail was heard until the deceased was buried, typically within 24 hours. These public laments were not merely emotional outbursts but a communal act of honoring the dead and expressing solidarity in grief.

This custom is vividly illustrated in the Gospel account of Jairus’ daughter. When Jesus arrived at the synagogue leader’s home, He encountered the characteristic scene of a Jewish household in mourning: “When they arrived at the house of the synagogue official, Jesus noticed a commotion, with people weeping and wailing loudly.” (Mark 5:38)

Such scenes were common in Jewish funerary settings and would have surrounded Jesus’ own death and burial. Recognizing these deeply rooted traditions allows us to appreciate not only the emotional atmosphere at the time of Jesus’ death, but also the theological and cultural weight His burial carried.

Among the mourning customs of ancient Israel, one notable practice was the hiring of professional mourners, typically women, whose role was to publicly lament and express grief on behalf of the bereaved. These women would wail, cry out, and sometimes sing dirges, heightening the emotional atmosphere of funerals and times of communal sorrow. The prophet Jeremiah directly refers to this custom: “Call for the mourning women to come; send for the most skillful of them. Let them hasten and raise a lament for us so that our eyes may overflow with tears and our eyelids run with water.” (Jeremiah 9:17–18).

This vivid, poetic portrayal reflects how ingrained these lamenting rituals were in the fabric of Israelite mourning culture.

Another expressive element of grief was the use of sackcloth (cilicio), a coarse, dark fabric typically made from camel or goat hair. Sackcloth was used to make rough garments—either worn alone or placed over existing clothing—as a visible sign of sorrow and penitence. This practice is the origin of the black mourning attire common in many cultures today.

For example, when Abner, commander of Saul’s army, was killed, King David ordered the people to mourn using traditional signs of grief: “Then David said to Joab and all the people who were with him, ‘Tear your garments, put on sackcloth, and mourn over Abner.’ And King David followed the bier.” (2 Samuel 3:31) The tearing of garments was another powerful symbol of intense sorrow or outrage. It was a public display of internal anguish, used in both personal and communal crises. We see this custom vividly in the Passion narrative, when Caiaphas, the high priest, reacts to Jesus’ declaration of His divine identity: “Then the high priest tore his garments and said, ‘He has blasphemed! What further need do we have of witnesses? You have now heard the blasphemy for yourselves.’” (Matthew 26:65)

In ancient Jewish tradition, it was customary to bury the dead quickly, typically on the same day of death. This urgency was driven by two primary reasons. First, the hot and arid climate of the Middle East led to rapid decomposition of corpses. Second, and perhaps more importantly from a cultural standpoint, delaying burial was considered a dishonor to both the deceased and the surviving family members.

This practice is evident in several biblical accounts. The Gospels and the Book of Acts record at least three instances where burial occurred on the very day of death:

- Jesus was buried the same day He died: “Joseph took the body, wrapped it in a clean linen shroud, and laid it in his own new tomb that he had hewn in the rock.” (Matthew 27:59–60)

- Ananias, after lying to the apostles, died suddenly and was buried at once: “When Ananias heard these words, he fell down and died. […] The young men came forward, wrapped up his body, and carried him out for burial.” (Acts 5:5–6)

- Stephen, the first Christian martyr, was also buried promptly after being stoned: “Devout men buried Stephen and made loud lamentation over him.” (Acts 8:2)

The custom of same-day burial also appears much earlier in salvation history. When Rachel, Jacob’s beloved wife, died during a journey, she was not brought back to be buried in the family tomb but was interred immediately: “Thus Rachel died, and she was buried on the road to Ephrath (now Bethlehem).” (Genesis 35:19).

Moreover, Jewish Law explicitly required the burial of executed criminals before nightfall, underscoring the dignity owed even to the condemned: “If a man is guilty of a capital offense and is put to death, and you hang him on a tree, his body must not remain there overnight. Be sure to bury him that same day.” (Deuteronomy 21:22–23). This commandment was fulfilled in the case of Jesus, who—though crucified as a criminal—was buried before sunset in accordance with the Law.

Ancient Jewish belief also held that the spirit of a deceased person lingered near the body for three days, listening to the mourners and remaining somehow “close.” After this period, it was thought that the spirit departed entirely and hope for restoration was lost. This cultural perspective appears in the narrative of Lazarus, when Martha, his sister, expresses her despair to Jesus: “Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, ‘Lord, by now there will be a stench, for he has been dead for four days.’” (John 11:39)

To this day, certain ancient burial customs remain in practice in parts of the Middle East, particularly in Syria. Among these traditions is the wrapping of the dead: the face is first covered with a scarf, and then the head, hands, and feet are wrapped in strips of linen cloth. In some cases—especially if the deceased was a person of status—the linen used may have originally been designated for wrapping sacred scrolls of the Law. Once wrapped, the body is carried to the grave and buried.

This practice sheds light on the resurrection of Lazarus, whose burial followed these customs. When Jesus called him from the tomb, Lazarus appeared still wrapped in the traditional funeral cloths: “The man who had died came out, his hands and feet bound with strips of cloth, and his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Unbind him, and let him go.’” (John 11:44)

The use of spices and aromatic substances during burial was optional and expensive, typically reserved for the wealthy. These materials helped mask the odor of decomposition and served as a sign of honor. Initially, myrrh and aloes were used; in later periods, other elements such as hyssop, perfumed oils, and rose water became more common.

A complete linen wrapping—such as the one used for Jesus—was not universally practiced but signified dignity and reverence. According to the Gospels, Joseph of Arimathea, a wealthy disciple, provided his own tomb and burial materials for Jesus, including an abundance of spices (John 19:39–40).

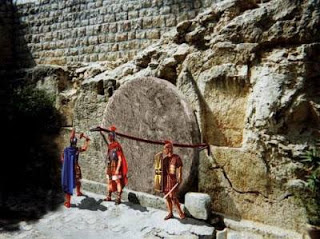

Tombs of that era were typically carved into rock and included a bench-like projection where the body was laid during decomposition. Once the flesh had decayed, the bones were collected and placed into an ossuary—a small container made of stone or clay. These ossuaries required little space and were often kept in family tombs, allowing the same burial site to be reused for generations.

Because of this repeated use, tombs were built with openable entrances. A large stone was rolled into place to cover the opening and protect the tomb, like the one that sealed Jesus’ burial place—a tomb belonging to Joseph of Arimathea.

It was also customary to whitewash the exterior of tombs during springtime, especially before the Passover. This made the tombs more visible and served to prevent ritual impurity, since accidentally touching a grave rendered a person unclean according to Jewish law (Numbers 19:16). This background illuminates Jesus’ powerful rebuke of the Pharisees: “Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! You are like whitewashed tombs which appear beautiful on the outside but inside are full of the bones of the dead and all kinds of filth.” (Matthew 23:27)

Had Jesus been buried like any ordinary stranger or pilgrim who died in Jerusalem, His body would have been placed in a simple grave in the ground, sealed permanently and never opened again. In such a case, the physical evidence of His resurrection—such as the stone rolled away and the linen burial cloths left behind—would not have been so striking or verifiable. These tangible signs gave early witnesses compelling confirmation that something extraordinary had occurred.

The open tomb and the remaining burial cloths served as silent but powerful testimonies to His resurrection, as foretold in Scripture. I will return to this point in greater depth later.

Historically, such ground burials were customary for servants, strangers, or the poor. For instance, Deborah, Rebekah’s nurse, was buried beneath an oak tree: “Deborah, Rebekah’s nurse, died and was buried under the oak below Bethel.” (Genesis 35:8). Many times, natural caves serve as family tombs. The Cave of Machpelah, for example, became the burial site for Abraham, Sarah, Isaac, Rebekah, Leah, and Jacob: “There they buried Abraham and his wife Sarah; there they buried Isaac and his wife Rebekah, and there I buried Leah.” (Genesis 49:31). Only prophets and kings were typically buried within city limits, which was seen as an honor. Samuel was buried at his home in Ramah: “Then Samuel died, and all Israel assembled and mourned for him. They buried him in his home at Ramah.” (1 Samuel 25:1). Similarly, David was buried in the city of Jerusalem: “David rested with his ancestors and was buried in the City of David.” (1 Kings 2:10).

In contrast, the poor were buried in a communal cemetery located outside the city walls, as noted in the reforms of King Josiah: “He removed the bones from their graves and burned them on the altar to desecrate it, in accordance with the word of the Lord. Then he returned to Jerusalem.” (2 Kings 23:6).

Jesus, however, received a burial befitting a man of great honor and wealth. The use of a linen shroud, the application of about a hundred Roman pounds (roughly 33 kilograms) of myrrh and aloes, and the placement of His body in a new tomb carved from rock—all indicate a burial of the highest dignity: “They took the body of Jesus and wrapped it with the spices in linen cloths, according to the burial custom of the Jews.” (John 19:40)

The tomb was donated by Joseph of Arimathea, a wealthy and respected member of the Sanhedrin, while Nicodemus provided the costly spices. These were not items that ordinary people kept on hand—especially at the onset of the Sabbath, when purchasing such materials would have been impossible.

What’s striking is that all burial rituals customary for the recent deceased were carefully observed in Jesus’ case. Yet no one involved in the burial anticipated that He might rise from the dead, despite the prophetic affirmations in the Psalms and in Jesus’ own words. The women and disciples who performed the burial rites believed they were preparing a body destined for long-term decay, not resurrection.

This makes the resurrection accounts even more credible. Why go through the costly, elaborate process of burial if the expectation were that Jesus would rise in three days? Why use expensive linen and perfumes if His return was imminent? The fact that they did shows they were not expecting an empty tomb. Only Mary, His mother, may have held that hope quietly in her heart.

Although the Gospels record no words from Mary during the burial, one can imagine that she recalled His repeated prophecies about His passion and resurrection. She shared them with those preparing the body, though they—like most others—did not believe her. This may explain why Mary did not participate in the burial rituals or accompany the other women on the morning of the resurrection. She may have been the only one who truly believed He would rise again.